Variable Frequency Drive Harmonics

For the AC power line, the system (VFD + motor) is a non-linear load whose current include harmonics (frequency components multiples of the power line frequency). The characteristic harmonics generally produced by the rectifier are considered to be of order h = np±1 on the AC side, that is, on the power line (p is the number of pulses of the variable frequency drive and n =1,2,3). Thus, in the case of a 6 diode (6 pulses) bridge, the most pronounced generated harmonics are the 5th and the 7th ones, whose magnitudes may vary from 10% to 40% of the fundamental component, depending on the power line impedance. In the case of rectifying bridges of 12 pulses (12 diodes), the most harmful harmonics generated are the 11th and the 13th ones. The higher the order of the harmonic, the lower can be considered its magnitude, so higher order harmonics can be filtered more easily. As the majority of VFD manufacturers, Iacdrive produces its low voltage standard variable frequency drives with 6-pulse rectifiers.

Thus, in the case of a 6 diode (6 pulses) bridge, the most pronounced generated harmonics are the 5th and the 7th ones, whose magnitudes may vary from 10% to 40% of the fundamental component, depending on the power line impedance. In the case of rectifying bridges of 12 pulses (12 diodes), the most harmful harmonics generated are the 11th and the 13th ones. The higher the order of the harmonic, the lower can be considered its magnitude, so higher order harmonics can be filtered more easily. As the majority of VFD manufacturers, Iacdrive produces its low voltage standard variable frequency drives with 6-pulse rectifiers.

The power system harmonic distortion can be quantified by the THD (Total Harmonic Distortion), which is informed by the variable frequency drive manufacturer and is defined as:

THD = √(∑∞h=2 (Ah/A1)2)

Where

Ah are the rms values of the non-fundamental harmonic components

A1 is the rms value of the fundamental component

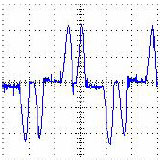

The waveform above is the input measured current of a 6-pulse PWM variable frequency drive connected to a low impedance power grid.

Normative considerations about the harmonics

The NEMA Application Guide for variable frequency drive systems refers to IEEE Std.519 (1992), which recommends maximum THD levels for power systems ≤ 69 kV as per the tables presented next. This standard defines final installation values, so that each case deserves a particular evaluation. Data like the power line short-circuit impedance, points of common connection (PCC) of variable frequency drive and other loads, among others, influence on the recommended values.

| Voltage harmonics | |

| Even components | 3% |

| Odd components | 3% |

| THDvoltage | 5% |

The maximum harmonic current distortion recommended by IEEE-519 is given in terms of TDD (Total Demand Distortion) and depends on the ratio (ISC / IL), where:

ISC = maximum short-current current at PCC.

IL = maximum demand load current (fundamental frequency component) at PCC.

|

Individual Odd Harmonics (Even harmonics are limited to 25% of the odd harmonic limits) |

||||||

| Maximum harmonic current distortion in percent of IL | ||||||

| ISC/IL | <11 | 11<h<17 | 17<h<23 | 23<h<35 | 35<h | TDD |

| <20 | 4 | 2 | 1.5 | 0.6 | 0.3 |

Negative sequenceNegative sequence will not cause a physical rotation. This component creates a field which, though not strong enough, tries to counter the primary field, An increase in this component will cause the motor to overheat due to the opposition. a physical rotation is not likely to occur. Negative sequence currents are produced because of the unbalanced currents in the power system. Flow of negative sequence currents in electrical machines (generators and motors) are undesirable as these currents generates high temperatures in very short time. The negative sequence component has a phase sequence opposite to that of the motor and represents the amount of unbalance in the feeder. Unbalanced currents will generate negative sequence components which in turn produces a reverse rotating filed (opposite to the synchronous rotating filed normally induces emf in to the rotor windings) in the air gap between the stator and rotor of the machines. This reverse rotating magnetic field rotates at synchronous speeds but in opposite direction to the rotor of the machine. This component does not produce useful power, however by being present it contributes to the losses and causes temperature rise. This heating effect in turn results in the loss of mechanical integrity or insulation failures in electrical machines within seconds. Therefore it is undeniable to operate the machine during unbalanced condition when negative sequence currents flows in the rotor and motor to be protected. Phase reversal will make the motor run in the opposite direction and can be very dangerous, resulting in severe damage to gear boxes and hazard to operating personnel. Why companies don’t invest in variable frequency drive controlInvesting in energy efficient variable frequency drives (VFD) seems like an obvious path to cutting a company’s operating costs, but it is one that many companies ignore. This article explores some possible reasons for this reluctance to invest in VFD. There is a goldmine of savings waiting to be unlocked by controlling electric motors, but the reluctance to take advantage of this is a very puzzling phenomenon. Motors consume about two thirds of all electrical energy used by industry and cost 40 times more to run than to buy, so you would think optimizing their efficiency would be a priority. The reality is that this good idea is not always turned into good practice and many businesses are missing out on one of the best opportunities to boost profits and variable frequency drive growth. It might surprise you to learn that your average 11kW motor may cost about £500 to buy but £120,000 to run at 8,000 hours per year over a 15-year lifetime (and that isn’t even accounting for inevitable increases in energy prices). It’s worth considering the payback on any investment in motor control that will reduce this significant running cost, such as using VFDs to control speed, or implementing automated starting and stopping when the motor is not needed. Payback times can often be less than 1 year and, of course, the savings continue over the lifetime of the system, particularly as energy costs rise. The question that often arises when I talk about this subject to people is: “If the savings are so great, why don’t more people do this?” It would appear to be something that fits into the nobrainer category, however there are three main barriers to the wider uptake of motor control with variable frequency drive, none of which should stop common sense from prevailing – but all too often they do. The first barrier is a lack of awareness of how much energy is being consumed, and where, in a business. A surprising number of companies do not have a nominated energy manager, still less have energy management as a dedicated job function or have a board member responsible for this significant cost. Those that do measure their energy consumption often have a financial rather than technical bias, so solutions tend towards renegotiating supply contracts, rather than reducing consumption. The second barrier stems from the economic climate and the level of uncertainty about future events and policies. Businesses are still reluctant to invest in improvement projects, despite short payback periods and the ongoing benefits. The short-term focus is on cutting costs, not on spending money, even to the detriment of future growth. This make-do-and-mend attitude is often proudly touted as a strength, but it is ultimately a false economy. Saving money by cutting capital budgets, reducing staff and cancelling training is damaging to a business and to morale, making it difficult to grow again when the opportunity arises. Saving money by reducing energy consumption makes a business more competitive, while keeping hold of key skills and resources. The third barrier is a focus on purchase cost, rather than lifetime cost. Whenever a business invests in a machine, a production line or a ventilation system, you can be sure they will have a rigorous process for getting several quotes, usually comparing price, with the lowest bid winning. Something that is not often evaluated is the lifetime energy cost of the system. Competing suppliers will seek to reduce the capital cost of the equipment but without considering the true cost for the operator, including energy consumption. What if the cost of automation and motor control added £700 to the purchase cost? Many suppliers will consider cutting this from the specification. But what if that control saved £1,400 per year in energy? It co Variable frequency drive saves energy on fansLike pumps, fans consume significant electrical energy while serving several applications. In many plants, the VFDs (variable frequency drives) of fans together account for 50% to 60% of the total electricity used. Centrifugal fans are the most common but some applications also use axial fans and positive-displacement blowers. The following steps help identify optimization opportunities in systems that consume substantial energy running the fan with VFDs. Step 1: Install variable frequency drive on partially loaded fans, where applicable. Any fan that is throttled at the inlet or outlet may offer an opportunity to save energy. Most combustion-air-supply fans for boilers and furnaces are operated at partial loads compared to their design capacities. Some boilers and furnaces also rely on an induced-draft fan near their stack; it must be dampened to maintain the balanced draft during normal operation. Installing VFDs on these fans is worthy of consideration. Similar to centrifugal pump operation, the affinity law applies here. Because constant-speed motors consume the same amount of energy regardless of damper position, using dampers to maintain the pressure or flow is an inefficient way to control fan operation. Step 2: Switch to inlet vane dampers. These dampers are slightly more efficient than discharge dampers. When a VFD can’t be installed to control fan operation, shifting to inlet vane control could provide marginal energy savings. Step 3: Replace the motor on heavily throttled fans with a lower speed one, if applicable. Smaller capacity fans with high-speed motor VFDs operate between 25% and 50% of their design capacity. Installing a low-speed motor VFD could save considerable energy. For example, a 2,900-rpm motor drove a plant’s primary combustion air fan with the discharge side damper throttled to about 75–80%. Installing a VFD on this motor would save considerable energy, but we recommended switching to a standard 1,450-rpm motor. This was implemented immediately, as 1,450-rpm motors are readily available. With the lower-speed motor, the damper can be left at near 90% open; the fan’s power consumption dropped to less than 50% of the previous level. Step 4: Control the speed when multiple fans operate together. Fans consume a significant amount of energy in industrial cooling and ventilation systems. Supply fans of HVAC systems are good candidates for speed control by variable frequency drives, if not already present. Step 5: Switch off ventilation fans when requirements drop. Ventilation systems usually run a single large centrifugal fan or several axial exhaust fans. A close look at their operation may indicate these fans could be optimized depending upon the actual ventilation needs of the building they serve. Recently, we surveyed a medium-sized industrial facility where 26 axial-type exhaust fans were installed on the roof of one building. All fans were operating continuously, even though the building had many side wall openings and not much heat generated inside. To better conserve energy, we suggested the 26 fans be divided into four groups with variable frequency drives controlled for each group. As a result, energy consumption for the fans dropped by about 50%, as only the required fan groups now are switched on. At another industrial site, the exhaust fan of a paint booth ran continuously but paint spraying was scheduled only about 50% of the time. Modifying fan operation with variable frequency drive and delayed sequencing saved energy. Pumps and fans are the most common energy-consuming devices Variable Air Volume System OptimizationVariable Air Volume Systems (VAV) can be optimized to increase energy savings by maximizing the efficiency of the equipment at part-load conditions. The goal with the optimization strategy is to run each subsystem (chiller, cooling tower, Airhandler, etc) in the most efficient way possible while maintaining the current building load requirement.

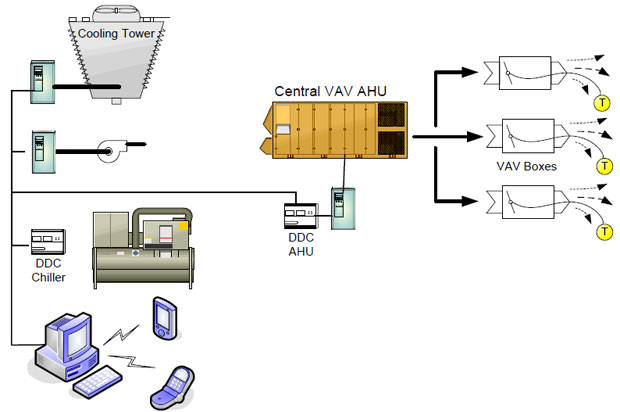

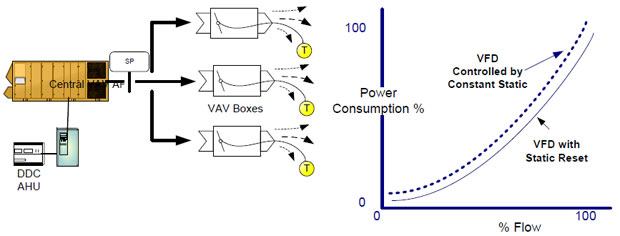

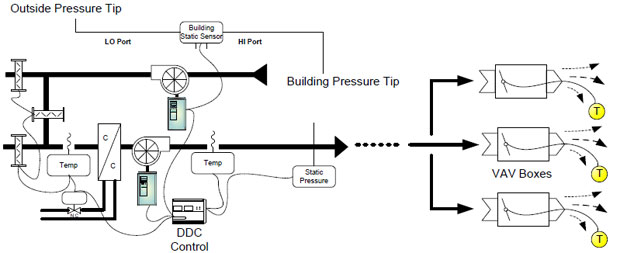

As each Variable Air Volume terminal controls the space temperature – based on flow the worst case zone can easily be identified by an automation system. The supply fan speed can be reduced by resetting the static pressure (see following page). As the load drops and the fan meets a preset minimum flow, the system resets the air temperature up, so less chilled water is needed. In a variable flow chiller system, this reduces pumping energy. If the system load continues to drop, the system will reset the chiller supply water temperature upward which will then reduce the energy requirements of the chiller. Changes in the chiller head pressure and loads can then reset the cooling tower fan speed. The key to optimizing the system operation is communication and information sharing through the entire system equipment. With the reduced cost of variable frequency drives and Building Automation Systems, (BAS) complete system optimization can be implemented as a cost effective option. In VAV systems where the individual VAV boxes and the AHU are on a building automation system, additional savings can be achieved by implementing static pressure reset. The static pressure sensor in a VAV system is typically located two-thirds of the way downstream in the main supply air duct for many existing systems. Static pressure is maintained by modulating the fan speed. When the static pressure is lower than the setpoint, the fan speeds up to provide more airflow (static) to meet the VAV box needs, and vice-versa. A constant set point value is usually used regardless of the building load conditions. Under partial-load conditions the static pressure required at the terminal VAV boxes may be far less than this constant set point. The individual boxes will assume a damper position to satisfy the space temperature requirements. For example, various VAV box dampers will be at different damper positions, (some at 70% open, 60% open, etc) very few will be at design, ie 95% -100% open. RESET STRATEGY With a lower static set point to maintain, fan speed reduces. The result is increased energy savings in the 3 to 8% range. See figure below. If the BAS system is already installed, implementing this strategy is relatively free. Power factor of a generator connected to national gridQ: What should be the power factor of a generator connected to national grid in order to have maximum stability? Whether it should be high or low? Steady State Stability: Transient Stability: Frequency Inverter Direct Digital ControlModulating Supply & Return Fans are used as a means of providing proper variable air volume (VAV) control as well as building pressurization. Many such VAV systems are still largely pneumatic with static to the downstream boxes being maintained by inlet guide vanes. To provide increased energy savings and energy comfort, these systems can be easily converted to frequency inverter fan control of the supply and return fans and Direct Digital Control (DDC) to coordinate any increased energy saving strategies. Figure 1 shows such a system.

To increase energy savings, the DDC controller can be programmed to reduce the flow from the return & supply fans for short periods of time. Coordinated with the building pressurization system, any temporary loss of space temperature may be avoided. In Figure 1, the supply fan is controlled by the duct static pressure sensor, via the DDC, while the outside air and mixed air dampers are optimized to provide economizer control.. The return fan is modulated to stabilize building pressure at a slight positive. For simple supply and exhaust systems the building pressure and static pressure sensors may be connected directly to the frequency inverter with an internal PID controller. Typical Energy Savings are realized from converting pneumatic (or electromechanical) control to DDC control with frequency inverter in the following ways:

CONTROL CONSIDERATIONS

Current transformer selectionWhen you want to select current transformer with appropriate rated power for your power system, you need to consider that value of rated power of selected current transformer should be higher from sum of values of load and Joules’ losses which are a consequence of flow current through conductors which connect current transformer with relay. So, if you have a long distance between current transformer and relay, then you need to consider one of two following manners for solving this problem: This solution is a consequence of necessity for reducing of Joules’ losses which are a consequence of flow current through conductors which connect current transformer with relay. If you have conductors whose value of rated current is 5A, you will have Joules’ losses P=R*I^2=R*5^2=25*R. Otherwise, if you have conductors whose value of rated current is 1A, you will have Joules’ losses P=R*I^2=R*1^2=R. Rotary Tube Furnace EfficiencyThere are many factors that govern the performance of rotary tube furnaces. A direct fired rotary unit has a potential for much higher thermal efficiency due to the direct contact of the hot gases with the material in process. Cement kilns are the most common large scale unit operation with direct fired units. Any articles you find on this will be helpful. Thermal efficiency can be estimated by dividing the inlet temperature minus the outlet temperature by the inlet temperature minus the ambient temperature in absolute scales either Rankine or Kelvin. Then there is the issue of co-current versus counter-current firing and heat recovery from the hot material and the exit gas for which standard designs are available. Indirect fired rotary kilns have heat transfer limitations due to the thickness and alloys needed for high temperature calcination >500 C. There is no simple way to measure the equivalent of the inlet and outlet temperatures on a direct fired unit. There are simply exit gas temperatures from each zone and an approximate shell temperature on the hot side of the shell which is lower than the zone exit gas temp. These are useful for control purposes and consistent operation. The higher the temperature the material requires to achieve conversion the higher the shell side fired temperature has to be to provide the delta T necessary to drive heat through the shell into the material zone. Some materials further limit heat transfer by adhering to the inside of the shell and acting as an insulator! This requires trial and error application of “knockers” at the ends of the shell or sometimes internally secured chains that bang around and knock the adhering material loose. This is a potential nightmare as the learning curve to install chains so that the securing lugs and the chains themselves will stay attached for acceptably long service before failing and ending up in the take off conveying equipment with usual breakage and downtime is an uncertain one. From Perry’s one can find thermal efficiencies for indirect fired rotary’s given as less than 35%. The bed fill can be 10-30% depending on the heat demand of the material and the heat transfer limitations. You will want to have real time gas usage metering on the burners so that you know the theoretical energy input. From that you can subtract the theoretical heat needed to complete your reaction and compare that to the input to see how efficiently you have used the energy input. The few large high temperature direct fired rotary kilns I have seen had view ports for measuring the local wall temperatures by optical pyrometer. It can be a challenge to get a protected thermocouple sheath down into the moving bed for an actual bed temperature and even just to hang it in the gas streams at the outlet or inlet area. See if you can contact cement kiln suppliers for some configurations of temperature sensing elements for your application. Bed fill effects on heat transfer are related to several parameters. Above ~500 C gas and refractory liner temperatures, the main heat transfer mode will be radiative as far as the surface of the bed material. Within the bed it will be conduction and some convection at the surface. A thin bed will reach max. temperature in shorter time, but this reduces through put for a given gas temperature. If you increase bed fill to increase production you will have to increase the firing temperature and the outlet temperature will probably increase lowering your thermal efficiency. This becomes a trade off between production rate and energy efficiency. Countercurrent firing usually maintains the highest driving force for heat transfer along the bed and gives the highest temperature of the bed just before exit of the bed material. Perry’s may have a useful section on direct fired rotary kilns and lime or cement manufacturing references may help you as well. Please make sure lead emissions to air are properly captured Calculate Capacitors PowerIn general, to calculate the necessary Power of Capacitors, we can use the following formula: Qc = P ( tgφ1 – tgφ2 ) where : In all cases, we should take into consideration the following points : 2- Be careful when compensate the PF of a Motor to avoid the Over-excitation case, but we can verify it by using the following formula : Qc (motor) = 2 x P (1 – Cos φ ), where : 3- After calculation of Qc, the choosing of Capacitors type will be done according to the Harmonic Distortion percentage. Noting that in some case where the Harmonic Distortion percentage is high, we should use ” Detuned Reactors ” with Capacitors, and when this percentage is too high, we can’t install the Capacitors before minimizing or eliminating the harmonics that their percentages are too high. |